We all have memories of being read stories as children. Tucked in our beds, these narratives floated in our imaginations as we drifted off to sleep. The story became the threshold between wakefulness and dreaming. In this exhibition, eight different artists address the bed or bedroom as an arena where stories, states of mind, and human drama play themselves out. In some cases the bedroom is a place of respite from the world and in others it is a place of isolation or conflict. For some of these artists the bed itself is the focus—suggesting the human presence in its absence or inviting us in and offering us a chance to rest or dream.

Shira Avidor portrays beds both empty and occupied by elusive figures. In Cot a spare bed in a dark room with the sheet turned down hardly seems welcoming. In her painting In Bed a conical “head” sticks out from under the covers. Is it human or ghost? In these images, where domestic comfort is turned upside down, “the idea of hominess,” as Avidor puts it, “crumbles apart.”

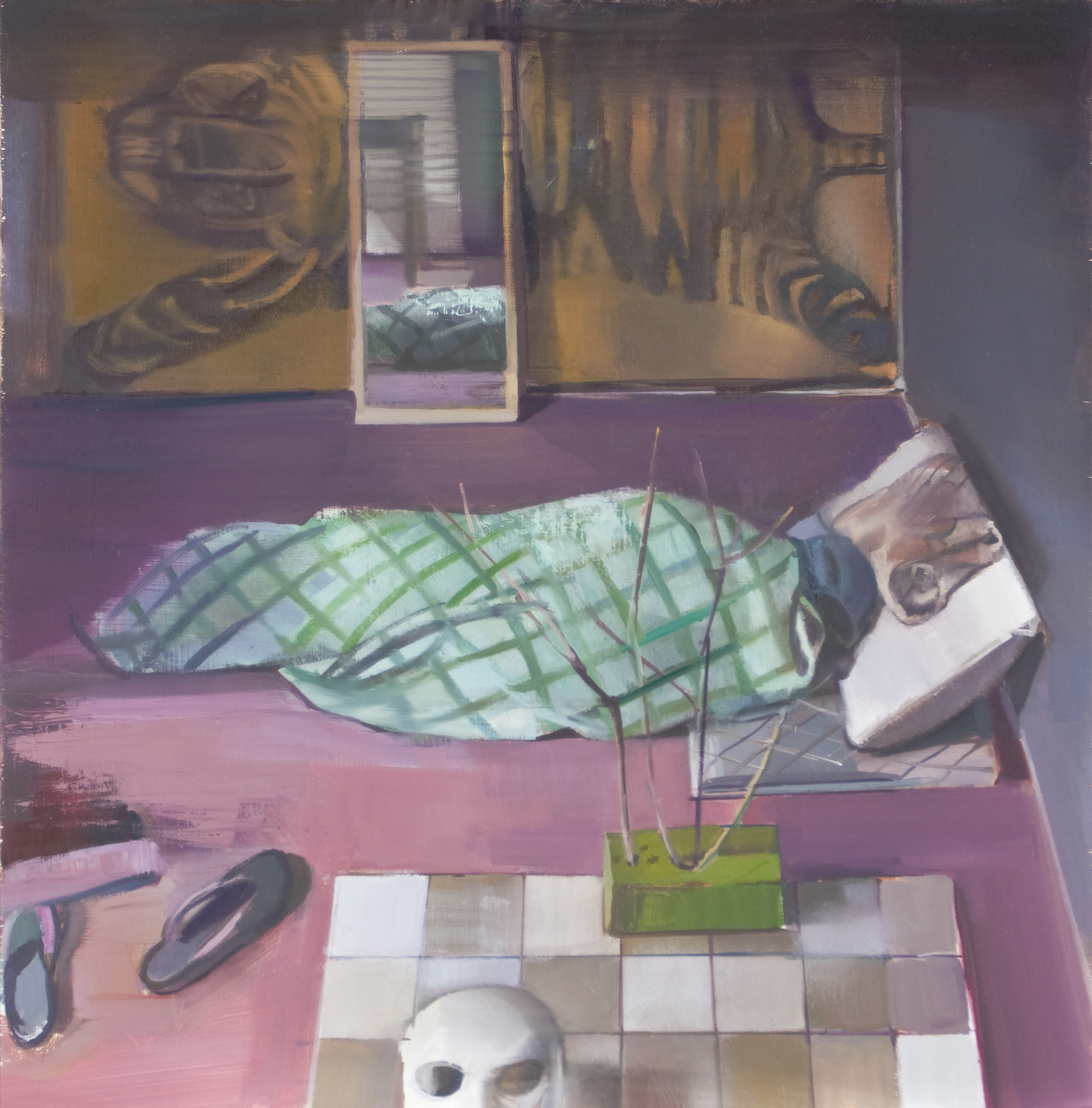

In her painting Faldum, Stephanie Pierce also portrays an elusive figure on a bed. The image is broken down into facets of color, planes and brushstrokes to the point where the figure and the bed become one. The work conveys a sense of things coming together and pulling apart at the same instant, like a dream state where nothing is fixed and everything is almost within reach.

Aaron Fink’s Pillow, a work never before exhibited, is likewise an object laden with meaning. Monumental in size, this painting of the humble bedroom accessory elevates its subject to an iconic status. The undulating brushwork echoes the soft folds of the pillow, but does it invoke comfort?

Another painting by Fink, the very early (1980) Bacchus and Ariadne, a different kind of story is being told. A man in a bathrobe, smoking a cigarette, stands before a reclining nude woman. Here, it is implied and is borne out by the title, the bedroom is a place of sexual conquest.

Two paintings by Cathy Lees also portray the bedroom as an arena where human needs and emotions are played out. In Dressing Dolls, a woman (the artist) sits on a bed engrossed in the act of doing just that. Another woman appears in the background dressing herself, although she is already fully clothed. In Undressing, the artist stands in front of the bedroom mirror beginning to undress, the doll now abandoned on the bed. The door to the room, previously opened, is now closed and the figure stands alone to confront her own reflected image.

Elizabeth Livingston and Suzanne Vincent both address the sleeping female is a way the evokes dreams and the unconscious. Vincent’s Snow White presents a young woman asleep amid bedding imprinted with images of the Disney cartoon character. We know from the original Grimm fairy tale that the story of Snow White touches upon the blurry boundary between sleep and death. In Vincent’s work, the crumpled Snow White goes head to head with the sleeping young woman. Will she be awakened by a prince?

The sleeping woman in Livingston’s Wedding Day will, as the title suggests, be awakened by her prince, at least metaphorically. Tucked under a billowy comforter, the morning light hitting her face, the coming day is all promise and potential. She luxuriates in her last restful moments. On the verge of moving from unconsciousness to wakefulness, she is also embarking on a life-changing event.

The serenity of sleep is also represented in Nanny Napping by Scott Prior. Portraying the artist’s wife reclining nude on their bed, Prior gives a quiet nod to the theme of the odalisque. Vulnerable in her nudity, and in her unconscious state, the sleeping figure inspires pathos. Is she aware of the gaze upon her?

Robert Knight’s series Sleepless was created by taking time lapse photographs of his young son in bed. Chronicling the movements of the child’s body, the shifting light patterns from a lamp and the rolling waves of bed linens, these photographs challenge our notion of what it means to “sleep like a baby.” And yet, through the blurring of form and light, creating the sense of something there but not there, Knight offers up a visual representation of the dream state.

Sleeping and dreaming are, of course, a part of life. Weaving our stories into the arena of the bedroom is a natural inclination. Whether the bedroom is a welcoming place or a dark, despairing one, there is a broad emotional spectrum to be explored. Sometimes we are glad to take to our beds, and sometimes we are grateful to wake up.